By Professor Dr jur, Dr phil Marc Weller, MA, MALD, PhD, FCIArb

We fear most what we do not know. An unexpected noise in the dark of night may inspire visions of menacing monsters in our minds. But when the light switch is turned, we see that it was nothing but a harmless butterfly knocking its wings helplessly against a window.

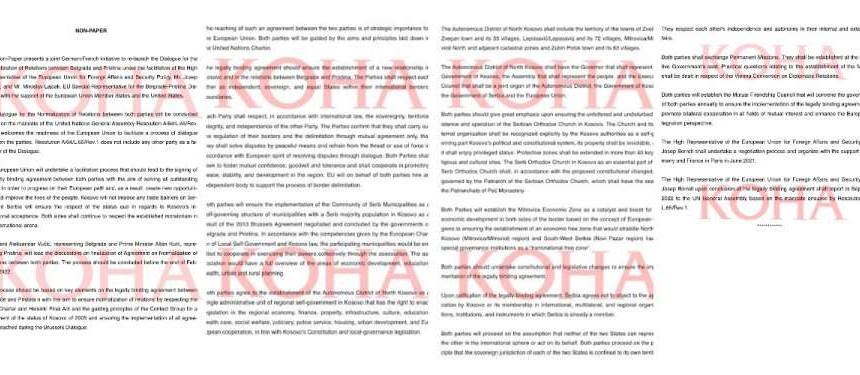

Kosovo foreign policy circles have been gripped by a sense of discomfort, if not outright fear. An unknown element has appeared, hiding its identity. It is a ‘non-paper’ written by an unknown hand, addressing the forthcoming normalization dialogue with Serbia

How can one be afraid of a piece of paper? And, all the more so, how can something that is not even a paper—a NON-paper—inspire such terror?

The answer is that in diplomacy, non-papers perform an important function. They allow a party to negotiations to float an idea in a way that is not attributable to anyone, including its authors. It is a way of testing out options and sounding out the likely response, before launching them more formally.

This time, the non-paper that seems to have started circulating out of nowhere addresses an issue of vital interest to Kosovo. It claims to represent a joint German-French initiative to re-launch the EU-led dialogue process on normalization of relations between Kosovo and Serbia. Germany has denied authorship. There are rumours that the document may or may not have come from the circle around the French President, somewhat to the embarrassment of his Foreign Ministry.

If the document comes from anyone other than the Belgrade government, then its appearance would indeed be quite concerning. The reason is simple—it rather reads as if it was drafted by President Aleksandar Vucic’s cabinet. If this really represents the approach by one of the key sponsors of the dialogue process, Kosovo will need to be on its guard.

Of course, the document may not be a serious proposal for the base-points of any negotiations between Kosovo and Serbia. Rather, it may have been designed as a ruse to rouse the freshly elected government under Prime Minister Albin Kurti into action.

PM Kurti famously declared this February, before he took office, that the normalization dialogue is low on his list of priorities. Rather, he will focus on the interests of the people who actually live in Kosovo, including its ethnic Serb population. Kosovo’s campaign to chase after diplomatic recognition by yet another Pacific island state may have sensibly come to an end.

Similarly, Kosovo’s fixation with membership in the United Nations and other international institutions should be overcome. Kosovo has managed to exist for a decade and more without membership and it can continue to do so without suffering significant negative consequences for a good while yet.

Elevating the issue of recognition by Serbia or by other states, and by international institutions, to a matter of life and death by Kosovo’s own politicians merely adds to the bargaining power of those who control the decision on recognition and on membership. Kosovo’s own exaggerated hankering after what lies in the gift of others only adds to the price it needs to pay for regularizing its existence in the international arena.

That said, Kosovo cannot afford to remain passive. In the past, the Kosovo authorities have waited until summoned to Brussels or other negotiating venues. There they were presented with a finalized agenda, and often with offers they could not refuse, out of deference to the USA or the EU, whether in the interest of the country or not.

This is not the approach one would expect from a mature state. Serbia would never expect to be engaged in this way. It would insist on taking a role in shaping the negotiating process, the format of discussion, the agenda of items to be discussed, and the sequencing of the talks. The negotiators in Brussels know this. Hence, they come knocking on Mr Vucic’s door already when preparing talks. Kosovo has in the past been mainly presented with the facts as agreed by the grown-ups between themselves and been told where to appear and when to discuss whatever the others have set out.

Kosovo is of course aware that a new effort at launching the normalization dialogue will be made soon, whether it is keen for this to happen or not. President Biden dropped the hint early this week, expressing his support for a renewed EU-led effort. Prishtina should ensure that this time, it is among the circle of those who design the process. In other words, it should exercise its sovereignty as all other states do.

This concerns not only issues of process in the negotiations. The famed non-paper, whether authentic or not, highlights the need for Kosovo also to shape expectations among the organizers of the talks, and its negotiating partner Serbia, in terms of actual substance.

In the past, Kosovo has gone through a laborious process of negotiating first internally, among the diverse political parties, with a view to obtaining agreement on a platform revealing its positions in the negotiations in some detail. This would then be endorsed by the Parliament. The purpose of this exercise was less to shape expectations outside of Kosovo, but more to achieve an internal consensus among the governing and opposition parties. This consensus would then be carried into the negotiations through the means of a unity-team representing all parties, or as many as would be willing to join in the effort.

This approach was in the past commended internationally, as it would ensure that any negotiating result could be ratified by parliament and enjoy broad support in the country. However, last time around, the Constitutional Court determined that appointing a unity delegation was not lawful. It found that a unity delegation would detract from the authority of the Prime Minister to lead a government and hence the negotiations. This finding was somewhat odd, as an institution of government is generally taken to be able to delegate functions to subordinate bodies it may create.

Now that there is a government that carries a majority in parliament, this ruling will come in handily. It allows the Prime Minister a free hand (subject to the constitutionally mandated consultations with the President) in shaping his negotiating strategy and in leading the process unencumbered by a persistent need to maintain a consensus among disparate actors.

There is no need to spell out Kosovo’s likely positions in the negotiations in great detail in advance, through a negotiating platform sanctified by parliamentary approval. However, what is needed at this moment is a commitment to certain base-points that must be understood by those preparing for the negotiations. That is why it is wise and necessary to respond at least informally to the supposed non-paper. If it remains unopposed, the thought might take hold that it could, after all, furnish a basis for the negotiations.

So what is wrong with the document, other than its uncertain origin to which no-one seems to be willing to own up at this point? First, there is the basic, underlying approach.

The document speaks of Belgrade and Pristina as the parties to the dialogue, in accordance with the ancient designation of the process as the ‘Belgrade-Prishtina Dialogue’ by the EU since its inception in 2011. History has moved on since then. While it would be unreasonable to expect Serbia to accept Kosovo as a state at the outset of the negotiations, it should by now be able to acknowledge that it is negotiating with Kosovo, even if it contests its status. The Washington Agreement of last September at least designates the sides as Serbia [Belgrade] and Kosovo [Pristina].

But the non-paper is behind its times in several other ways. It does not mention with one single word that Kosovo has already successfully gone through very involving negotiations during the Ahtisaari process, and that it accepted all of the painful concessions it had to make in order to obtain statehood. It has already paid the price for independence, as it were, and cannot be expected to start again, offering a second helping to Serbia, for the prize it has already won.

Instead, the non-paper curiously refers to the OSCE Paris Charter and Helsinki Final Act as standards to be respected in the legally binding agreement that is to be reached. This is normally understood as a diplomatically veiled reference to the territorial integrity of a state, in this instance, Belgrade’s view that Kosovo is part of Serbia.

More strange, still, is the requirement that a settlement is to be obtained according to the ‘guiding principles of the Contact Group for a settlement of the status of Kosovo of 2005.’ This provision entirely disregards the fact that, since then, the Ahtisaari negotiations were completed, Kosovo obtained independence in full accord with the Ahtisaari document, and that the International Court of Justice confirmed the lawfulness of its declaration of independence. Indeed, all members of the Contact Group other than the Russian Federation have long recognized Kosovo as a state. It seems incredible that Kosovo should now return for guidance on its the status to the views of the Contact Group uttered in 2005.

The non-paper does not expressly provide for recognition of Kosovo by Serbia as one of the essential outcomes of the process. Instead, it refers to a ‘new relationship’ between Belgrade and Prishtina. Still, it requires that ‘the parties shall respect each other as independent, sovereign, and equal States within their international borders/boundaries,’ and they shall ‘respect in accordance with international law, the sovereignty, territorial integrity, and independence of the other party.’ This does in fact amount to recognition, although by another name. Moreover, the non-paper provides for the exchange of diplomatic missions in accordance with the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic relations. This actually goes beyond recognition by establishing formal diplomatic relations between the two states according to international law.

The paper also provides for constitutional and legislative changes to be adopted by the sides to ensure the implementation of the legally binding agreement. Presumably this includes the requirement that Serbia will need to give up its constitutional provisions claiming to be the sovereign over Kosovo. However, the requirement for constitutional change also appears to affect Kosovo as the non-paper foresees extensive changes to its internal organization that cannot be squared with its present constitution.

With respect to membership in international organizations, the non-paper suggests that Serbia would no longer object to Kosovo’s application for membership in international institutions in which it is a member once the agreement has been ratified. One may ask whether an obligation of non-obstruction, instead of pro-active facilitation or at least support for membership, would suffice.

Indeed, Kosovo might well propose that any normalization agreement would only enter into force once membership in the UN and possibly other institutions has actually been achieved. This would ensure that Kosovo is not left, once more, to pay the price for a settlement, while Serbia alone collects the benefits. For instance, it is possible that Russia, which holds a veto over the matter, might still obstruct Kosovo’s UN membership, even if Serbia no longer (openly) opposes it.

Then there is the vexed issue of the Association of Serb Municipalities. The document points to Kosovo’s commitment in the 2013 Brussels agreement, which provided that participating municipalities would be entitled to cooperate in exercising their powers through a Community/Association collectively. That Community/Association would have ‘full overview’ of the areas of economic development, education, health, urban and rural planning.’

The Kosovo Constitutional Court has placed certain restrictions on the implementation of this provision—a provision which, admittedly, Kosovo freely accepted. However, since then, the Kosovo authorities have hovered, failing to implement their commitment according to their own interpretation of the 2013 Brussels agreement and the interpretation offered by the Constitutional Court. Rather than adopting their own version of this commitment in Kosovo law, the issue has now been consistently been raised by the EU and Belgrade as an example of Prishtina’s failure to live up to its own obligations.

Worse, rather than disposing of this issue through its own law, the non-paper now transports this issue onto the terrain of the upcoming negotiations. The EU Special Envoy has already demanded that Kosovo should change its constitution in order to accommodate a more far-reaching interpretation of the commitment to the establishment of the Association of Serb communities. This risks creating a third layer of governance, or parallel governance, in Kosovo—a proposition that had been consistently rejected during the Ahtisaari process.

In fact, the non-paper goes beyond proposing just one additional layer of authority in the shape of the Association of Serb municipalities. The document incredibly proposes the establishment of an autonomous District of North Kosovo as a single unit of regional self-government in Kosovo. The region would be large. It would encompass the towns of Zvecan and its 35 villages, Leposavic and its 72 villages, and Mitrovica North and adjacent cadastral zones and Zubin Ptok town and its 63 villages.

The non-paper foresees that this region would have its own elected assembly and its executive council administering it as one single unit. It would exercise broad powers of self-government, beyond the scope of the jurisdiction of the Kosovo government. In addition to a representative of the Government of Kosovo and of the Northern District, there would be representation of Serbia and the EU in the executive council. In other words, the territory would be subjected to internationalized governance with the direct involvement of the government of Serbia. Serbia, or course, has thus far funded and administered the structures of parallel government in Northern Mitrovica, encouraging the local population to resist any manifestation of Kosovo’s sovereign authority in that region. And it is an unshakable principle that after its experiences during the war, Kosovo could never return to the exercise of authority by Serbia on its territory.

A further element of the non-paper concerns the Serbian Orthodox Church. Again, the paper proposes a further layer of independent authority, enjoying a ‘privileged status.’ The Serb Orthodox church is to function as a ‘self-governing part’ of Kosovo’s political and constitutional system, governed by the Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church at Pec Monastery. This comes close to Belgrade’s vision of an extraterritorial status for the various sites of the Serb Orthodox church, analogous to the arrangements of Mount Athos, but dotted about Kosovo’s territory.

Again, the document is entirely silent about the fact that the Serb Orthodox Church, its sites and structures and personnel, already enjoy the most advanced protection one might imagine under the provisions of the Ahtisaari document. These provisions have been faithfully enshrined in Kosovo legislation. This includes the system of special protective zones around Serb Orthodox heritage.

The challenge is less to add yet more layers of protection and separation of these sites from Kosovo. Rather, the question is how the Serb Orthodox authorities might be encouraged ever so gently and over time to accept that they live and operate (entirely freely) in Kosovo. They will ultimately need to work with the Kosovo institutions in preserving the heritage sites and ensuring that they flourish as part of their local communities, rather than in isolation from them. In addition to their special significance to the Serb Orthodox Community, these sites are also part of the heritage of Kosovo, whose population is becoming increasingly alienated from them.

In sum, the non-paper should alert the Kosovo authorities to the thinking that may be pursued by external actors involved in the normalization process. On the plus side, the document does go a fair way in requiring Serbia to accept Kosovo as a state. While it stops short of using the term ‘recognition,’ it does in substance provide for it, along with the establishment of diplomatic relations on the basis of international law. Moreover, the requirement for Serbia to abandon its claim to Kosovo in its constitution is at least hinted at.

On the negative side, the instrument reflects the air and attitude on paternal imposition. It disregards Kosovo’s actual existence as a state for over a decade, recognized by over 100 other states. Rather, it expects Kosovo to pay once more for the privilege of statehood. Most importantly, this relates to the dilution of Kosovo statehood at three levels. First, there would be pressure in favour of an exaggerated version the Association of Serb municipalities, creating a further layer of self-governance largely removed from Kosovo’s jurisdiction. Second, it would establish the Northern Region or District as a single unit under its own administration, almost entirely removed from Kosovo’s jurisdiction. It would be placed under internationalized supervision with direct involvement by Serbia. Finally, there would be further separation of Kosovo from its Serb Orthodox heritage.

This approach represents an entirely antiquated approach of ethnic separation and of layering of autonomy upon autonomy. This approach was pioneered in the wake of the ethnic conflicts of 1990’s. It is generally believed to have failed in delivering ethnic reconciliation and functioning multi-ethnic states. Bosnia and Herzegovina offers the best example of this internationally-induced failure.

Of course, the non-paper may well be a hoax of some sort. It seems hardly credible that it could have been put forward, even as a trial balloon, with any sort of serious intent. But its existence should lead the Kosovo government to formulate a number of basic principles that will inform its attitudes in the forthcoming negotiations.

The government is right in not pressing for a rapid return to negotiations. Nevertheless, it needs to shape the process and basic expectations for the talks which will, in the end, come about. It needs to communicate that it is not negotiating Kosovo’s status. That stage is long past and Kosovo’s statehood is not an issue. Kosovo is not willing to make yet more concessions in order to obtain what it already has—statehood. As the title of the talks suggests, Kosovo is instead willing to discuss in good faith normalization of relations in the common, reciprocal interest of both parties.

Marc Weller is Professor of International Law and International Constitutional Studies in the University of Cambridge and author of Contested Statehood: Kosovo’s Struggle for Independence, Oxford University Press, 2009. He served as an advisor for Kosovo in the Ramboulliet and the Ahtisaari negotiations.